Remember when your parents used to tell you that playing video games would “rot your brain?”

Well, they were wrong about that. However, if your particular set of parental units used the term “warp your brain” instead, they’d have been on the right track.

In the last few decades, brain scientists have learned a lot about something called neuroplasticity. Essentially, the brain changes its physical configuration in response to the tasks you give it and the stimuli you expose it to.

This can include something as simple as using a clock to something as complex as playing a video game. It can also include using the internet.

Over the past few years, I’ve had a sneaking suspicion that my daily internet use was having consequences on the way I think. I used to be able to immerse myself in a book and read for hours; now, that sort of task seems a lot harder.

I also seem to remember spending a decent amount of my time bored when I was a kid. Now, boredom almost never creeps into my life. There’s always something new grabbing for my attention.

It turns out this suspicion wasn’t misplaced. Like the clock, the video game, and countless other technologies, the internet quietly changes the structure of our brains as we use it. And the results aren’t always positive.

So today, let’s explore just how the internet affects our brains — and what we can do to prevent, or reverse, its most harmful changes.

Our Tools Work on Us

In the late 1800’s, the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche’s eyesight began to fail him. And this had a terrible consequence – it made it almost impossible for him to write. The act of focusing his eyes on a page while writing gave him horrible headaches, and he started to worry that he’d have to give it up entirely.

But something saved him, and that something was called the Malling-Hansen Writing Ball. As weird as this thing looks, it was actually the fastest typewriter ever built when it was released, and it saved Nietzsche’s writing career. Once he learned to touch type, he could write with his eyes closed.

The Writing Ball didn’t just rescue Nietzsche’s ability to write, though — it also changed the character of his output. One of his close friends noted that Nietzsche’s writing took on a new forcefulness; it felt tighter.

Nietzche agreed, writing,

“You are right. Our writing equipment takes part in the forming of our thoughts.”

And it’s not just our writing equipment that does this. In the book The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains — which was the primary source for this article — author Nicholas Carr demonstrates how nearly all of the technology we use can cause actual changes in our brains.

For example, one experiment done on violin players showed that the area of their sensory cortexes that controlled their fingering hand was much larger than that of people who had never played a musical instrument.

The London Cab Driver Experiment

But it’s not just the physical use of tools that can cause these changes. Even purely mental activity that’s shaped by technology can do it.

Another experiment on London cab drivers found that, compared to a control group, the area of the drivers’ brains called the posterior hippocampus was much larger than normal. As you might expect, this is a part of the brain that plays a huge part in helping us understand our physical surroundings.

Now, it’s no big surprise that a cab driver’s brain will adapt to the task of navigating a complex web of city streets when that’s what they spend all day doing. But other technologies have far subtler — and further reaching — effects.

Your Brain on Technology

Before the invention of the clock, humans perceived time very differently than we do now. To them, time flowed like a stream of water; the transition from one moment to the next was seamless and imperceptible.

Once people started tracking time, that all changed. When we invented the first time-keeping devices, we changed our conception of time itself. Instead of being an unbroken stream, time was now a series of discrete, individual units.

As clocks become more and more accurate, these units got smaller and more precise. Suddenly, we started thinking in terms of hours, minutes, and eventually, seconds. We also started fixating on productivity — time spent, time wasted.

Time Changes Everything

But there was a much larger effect as well. Once we started perceiving time as a construct made up of small, discrete parts, that thinking was extended to everything else as well. As Carr writes,

“Once the clock had redefined time as a series of units of equal duration, our minds began to stress the methodical mental work of division and measurement. We began to see, in all things and phenomena, the pieces that composed the whole…the clock’s methodical ticking helped bring into being the scientific mind and the scientific man.”

And if the clock made a big change to the way we think, writing made an even bigger one. It took thousands of years for writing to progress through the necessary stages — the shift from logographic characters to phonetic alphabets, the addition of spaces between words, and the invention of the Gutenberg press, to name a few — but eventually this technology led to a huge shift in our behavior.

Once the general population became literate, they started to read — silently — for long stretches of time. And this was a bigger deal than you might think.

Carr writes, “To read a book was to practice an unnatural process of thought, one that demanded sustained, unbroken attention to a single, static object.”

And for people to do this, they had to forge neural pathways that would allow them to apply “top-down control” over their attention.

Top-Down Control Takes Over

Top-down control is something that has to be learned and practiced. By default, we’re built for “bottom-up” attention — our senses are finely tuned to pick up changes in our environment, and our attention naturally drifts to those changes.

This is great for keeping an eye out for lurking tigers or potential sources of food, but it’s not so great for deep, analytical reading. It doesn’t allow for the type of intense, prolonged concentration that’s necessary for parsing complex ideas.

Through reading, we developed a new type of attentional control — one that was much better suited to that task.

And it seems that now we’re starting to lose that ability.

The Internet Seizes Your Attention and Scatters It

Let’s revisit that experiment with the London cab drivers for a second — because there’s something I didn’t mention before.

In addition to the enlargement of the posterior hippocampus in their brains, the researchers also noticed a change in the anterior hippocampus — it shrank. And when they ran more tests, they found that this shrinking may have hurt the cab drivers’ ability to perform other memorization tasks.

Norman Doidge’s words come back to mind — when we stop using certain skills, the neural pathways that used to support them get reconfigured to enhance the skills we do use. As the psychiatrist Jeffrey Schwartz puts it, it’s “survival of the busiest.”

You can see where this is going — unless, of course, you’ve already gotten distracted and have clicked away from this article.

The technology that we now spend most of our time using — the internet — definitely doesn’t encourage the use of neural pathways that are devoted to top-down attentional control and long-term concentration on a single object.

Carr puts it well:

“Our use of the Internet involves many paradoxes, but the one that promises to have the greatest long-term influence over how we think is this one: the Net seizes our attention only to scatter it.”

The Internet Encourages Multitasking

The internet promotes distraction and multitasking. We almost always have multiple devices at hand that can access it.

Even using one computer, you can still watch a video, have 18 other tabs open, play Spotify in the background, and get notifications from Slack and iMessage at the same time.

Moreover, the internet rewards this distracted behavior. It’s not just our frequent use of this technology that gives it such a powerful ability to shape our neural pathways — it’s also the fact that using the internet offers constant, quick dopamine hits.

Every time you check Twitter or Instagram, there are new mentions, comments, and photos waiting for you. Every time you look at the sidebar on YouTube or on most blogs, there are interesting headlines that make your eyes light up.

The result is that the internet encourages the return of our natural, “bottom-up” style of attentional control. There’s always something new happening, somewhere else to shift your focus. And, just as with the cab drivers, your brain has to give something up.

The more you allow the internet to promote this distracted, frenzied style of consuming information, the less time you spend deeply concentrated on one task — and the less able you are to call up that deep concentration when you really need it.

So…what can we do about this? Are we stuck in a downward slide, doomed to end up like the people in Idiocracy?

Or can we reverse the trend?

10 Ideas for Reclaiming Your Attention

Remember, it’s “survival of the busiest.” The key isn’t to simply stop using the internet. It’s to reduce the activities that change your brain in undesirable ways, and replace those activities with ones that promote the neurological changes you want to happen.

This could mean that you don’t even need to stop using the internet at all! There are lots of long-form articles, long video essays, and other deep content on the web. Hundreds of thousands of scientific papers can be accessed.

And through apps like the Kindle Cloud Reader and projects like Gutenberg Books (Android | iOS), you can read millions of books from any internet-connected device.

But remember that the brain seeks out rewards, and the internet doles out the ones that promote distracted thinking.

If you’re sitting in a chair reading a print book with your phone in the other room, it’s pretty hard to give in to the temptation to send a tweet or check your email — meaning those neurological circuits don’t get strengthened.

But it’s quite a different story when you’re reading the same book on your computer, or even on your internet-connected iPad.

So we need to do two things:

- Promote the healthy activities that build top-down attention control.

- Make environmental changes that make it easier to shake our bad internet habits.

Here are 10 ideas to help you do both:

1. Read More Books

Sure, people will make the argument that a lot of books are full of filler, and that you could get the same salient points through a summary or a well-written article.

But this argument isn’t relevant here; the goal of reading books is to promote deep, long-term concentration on one thing.

And though there do exist many books chock-full of filler, there are also plenty of worthwhile books to be found as well.

2. Spend Time Working Without the Internet

Yes, the internet is a very useful tool — but you don’t always need it. Some of my best research has come from browsing library books, and many of my work tasks — writing, editing video, etc — don’t require the internet at all.

My brain is trained to believe that I need it — in fact, I feel cut off without it — but more than anything, that’s a sign that I need to let those neurological circuits fade a bit. Currently, I’m dependent on the internet, and it’s not healthy.

3. Have More In-Depth, In-Person Conversations

One of the best ways to do this is to go out to dinner with your friends.

And once you get there, put away your phone. Don’t even leave it on the table next to you — you’ll just end up tempted to check it. Put it away and focus on the amazing humans sitting right in front of you.

4. Watch More Movies

The idea here is the same as reading books. Instead of hopping to a new YouTube video every five minutes, you spend around two hours focusing on one piece of media. Put away your phone when you’re doing this for maximum immersion.

5. Spend Longer Periods of Time Focusing on One Thing

Go ride your bike for a full hour. Play an instrument for a full 30 minutes. Take 45 minutes to organize your Magic: The Gathering cards into color-coded sleeves.

Don’t think you have enough time to spend on these kinds of leisure activities? Use RescueTime to see how much time you waste online each day — it’s likely that it’s more than that hour you could have spent out on your bike.

6. Watch YouTube Videos in Full-Screen Mode

I almost never do this, and it’s kind of baffling as to why. After all, the video will clearly look better if it’s taking up the whole monitor.

But the reason is clear when you understand neuroplasticity, our reward-seeking behavior, and how YouTube is designed; though I’m ostensibly watching the video, my brain is also itching to click on the next interesting thing in the sidebar.

Want to take this even further? Here’s a little bit of CSS code I wrote that will actually blur out all the suggested videos on YouTube. Take that, attention-sucking algorithms!

7. Read Articles in Reader Mode

Most websites are filled with sidebar links, pop-ups, and other UI features meant to grab your attention and keep you jumping from page to page. Using reader mode gets rid of all these elements and leaves you with nothing but the article you want to read.

Safari on iOS and Chrome on Android both have built-in reader modes. On the desktop front, Firefox, Safari, and Microsoft Edge have each had one for years, and Chrome is working on adding one (though it’s still experimental as of this writing).

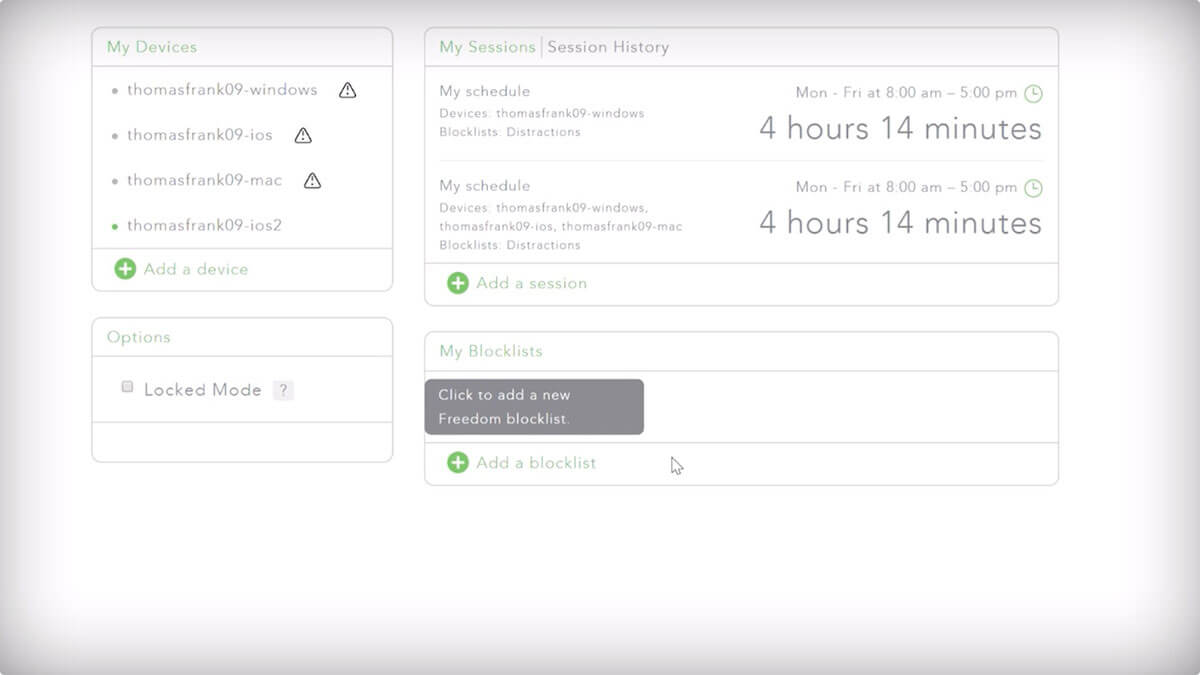

8. Limit Your Time on Distracting Websites

Instead of using social media, email, and other distracting apps all day, compress everything you do with them to just one hour.

This is quite easy to accomplish, actually. You could, of course, just disable your Wi-Fi or unplug your computer’s ethernet cord during the other hours of the day.

But you could also use a website blocker like Freedom to set up blocklists and periods of the day when they’re disabled.

Find your phone especially distracting? Here’s how to change that.

9. Make Social Media Sites Less Distracting

Social media sites are designed to suck you in and distract you. But there are ways to fight back! For instance, News Feed Eradicator (available for Chrome and Firefox) hides your Facebook timeline when you’re browsing on your desktop.

You can also simply create bookmarks to Messenger and your profile, bypassing the news feed page altogether.

On the Twitter front, free tweet-scheduling apps like Buffer can let you tweet without actually going into the Twitter app and getting sucked into the feed.

10. Hide the Visual Clutter in Your Browser

If you’re anything like me, you probably have a bookmarks bar, Extensions, and OS taskbar visible when you’re using the internet. These just clutter up your screen and offer more opportunities for distraction.

To free up your attention, you can hide all of these interface elements. If you ever do need to access any of these apps when you’re working, you can always browse to them manually.

What you’ll find, however, is that you generally don’t need to switch between apps or web pages while doing work. It’s just another distraction.

Regaining Focus Requires Time and Discipline

These tactical changes aren’t going to wean your brain off its internet-addicted habits on their own, but they’ll go a long way to helping you do that more easily.

Still, remember that the process of changing your brain’s most frequently-accessed neural pathways is a slow one that requires a lot of discipline at first.

So, once you’ve set these things up, focus more on the positive habits we talked about earlier – reading books, having deep conversations.

Eventually, that ability to focus deeply will come back.

For more about how the internet is affecting your brain, check out our article on mental laziness.