If you regularly find yourself running late, I’ve got a few tips for you today that should help you solve that problem.

Before we get into the five tips I’ve got for you below, let’s first answer the question: Why are people late?

Disregarding people who are always late simply because they’re disrespectful poopheads (to use the technical term), here are the main factors that cause people to be late:

- Inaccurate time estimates: Humans are pretty bad at estimating how long things will take. We’re pretty susceptible to the Planning Fallacy, which describes how our predictions are almost always overoptimistic.

- Procrastination: When the thing we’re doing now is enjoyable – that is, when it’s activating the brain’s reward center – we tend to push off the next task (such as getting ready to leave for work). It’s the, “One more minute!” excuse that every kid uses to keep playing Pokemon instead of going to bed.

- Forgetfulness: Sometimes we straight-up forget things we’re supposed to do.

So how we fix these problems? Here are my tips, starting with a couple methods for fixing the first problem – our inability to make good time estimates.

Envision the Entire Sequence of Steps

Imagine yourself going through the whole process, starting from right now and ending with you actually doing the next thing you’re scheduled to do.

Doing this helps to counteract the Segmentation Effect, which describes how people’s time estimates for one whole task are always smaller than the sum total of the time estimates for each individual sub-task when the whole task is broken down. This happens because we overlook many of the smaller steps in a process; our brains like to focus on the parts that take the most time.

Here’s a perfect example: When I need to go somewhere, my brain naturally fixates on the transit time – how long it’ll take to move myself from Point A to Point B. My default inclination is to make a time estimate based only on how long that takes.

That’s a mistake that can easily force me to send one of those all-too-common “Prolly gonna be 5 minutes late” texts.

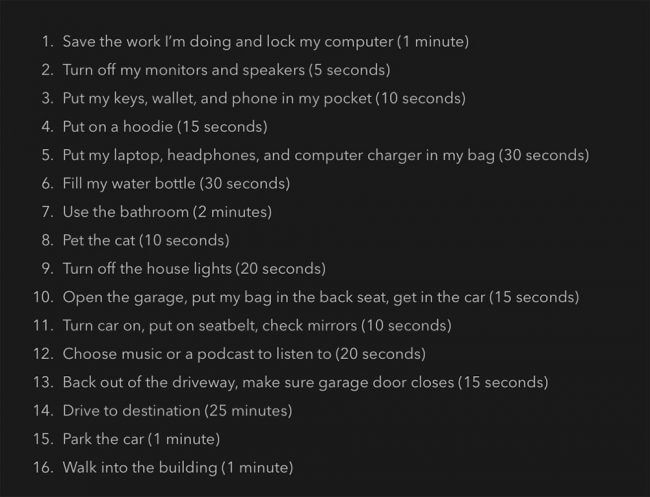

Even though a 25-minute drive might be the longest step of the process, it’s not the only step. There’s a lot more involved that tends to get overlooked. The whole thing might look something like this:

Pretty substantial when you think about it, no?

There are 15 other steps, all adding up to an extra 490 seconds (more than 8 minutes) of time. Rather than budgeting 25 minutes to get to my destination, I needed to budget at least 33–34.

Utilize a Fudge Ratio

In reality, I should probably budget more than 33-34 minutes if I truly want to get to where I’m going on time. Remember, I’m a human, just like you. Not a robot – would I lie to you? Beep boop-erhm, I mean… golly, isn’t breathing oxygen great?

So as a fellow human, my brain is susceptible to the Planning Fallacy, which means my initial estimates are likely to be overoptimistic. This is a natural quirk of the human brain, and it happens because we tend to plan only for the best possible scenario.

Research has proven this: Psychologists at the University of Waterloo in Canada asked people to give two types of time estimates for completing tasks:

- Best guess – AKA the normal, everyday scenario

- Best case – AKA the ideal, perfect scenario where everything goes just right

The results of this research, which were published in the aptly-titled paper People Focus on Optimistic Scenarios and Disregard Pessimistic Scenarios While Predicting Task Completion Times, can be summed up well with this quote from the paper’s conclusion:

“Our evidence is unequivocal: Writing pessimistic scenarios did not reduce predictors’ optimism about when their tasks would be completed.”

In other words, estimates for both types of scenarios were virtually identical; even when asked to picture a non-ideal scenario, people remain over-optimistic. We simply don’t plan for the grandma driving in front of us at 5 mph, or any of the other things that can and will go wrong.

Even though history (and common sense) prove that there’s a natural distribution of event outcomes, our brains still fixate on the small portion that go perfectly and plan as if they’ll always happen.

So, how does one overcome this built-in brain bug? I’ve found that, with ample time and deliberate practice, you can start naturally making realistic predictions. The way you do this is by building a revision step into your brain’s prediction-making process, so that your initial prediction is automatically adjusted before you consciously commit to it.

Here’s how this works in my brain:

“Ok, it’ll probably take 20 minutes to catch all the fish in this lake with my bare hands, Actually, that’s probably overoptimistic – it’ll be more like 28 minutes.“

At first, I had to go through this revision step consciously. I’d make a prediction, then deliberately tell myself that it was too idealistic; then, I’d pad it out a bit in my head. Since I was also doing my best to break down tasks into individual steps, the process looks something like this:

- Break the task into individual subtasks

- Make a time prediction for one subtask

- Revise that prediction – pad it out a bit

- Repeat steps #2 and #3 for each subtask while keeping a running total

- Arrive at a (hopefully) accurate time estimate

Since I’ve been doing this for a long time, the process has become more-or-less automatic at this point. I no longer have to mentally go through the aforementioned algorithm step-by-step; my brain has turned it into a habit.

While that doesn’t mean I’m perfect at making time estimates, I’ve noticed that the ones I make now are accurate much more often than they used to be.

If you’re not at the point where going through a revision step is second nature, a great interim solution for making better estimations is using a Fudge Ratio, which I learned about from the writer Steve Pavlina (though I’d bet people have been using similar concepts for decades).

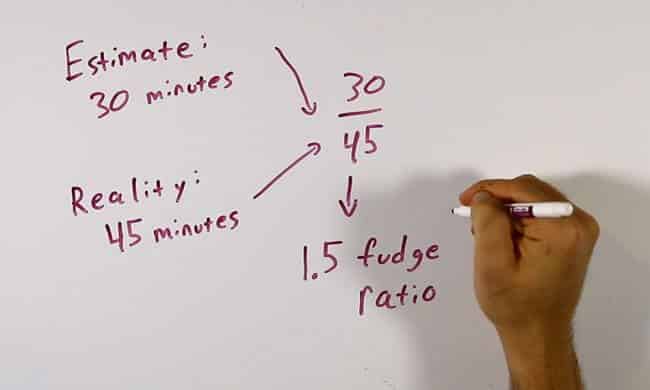

The Fudge Ratio is simple: It’s the difference between your estimation and reality. If you guessed that it’d take 30 minutes to get to class from your apartment, and it actually takes you 45, then your Fudge Ratio for that task is 1.5.

Pavlina recommends recording your estimates and resulting outcomes for several tasks of similar nature, which will give you enough data to obtain a good average. From there, you can use the resulting Fudge Ratio for similar tasks in the future – i.e. the next time you estimate it’ll take you 15 minutes to get somewhere, you’d toss in the Fudge Ratio and go with an estimate of 23.

One last thing I’ll mention here is that if you have enough data about the completion times of a particular task, you’d probably be better off using reference class forecasting – which is a fancy statistician’s term for saying:

“If it took an hour last time, it’s gonna take an hour this time.” – says the farmer as he hands you the manure shovel

Basically, if something you do has a very consistent completion time, it’d be wise to use that time as your estimate for doing the same task in the future.

I use RCF for a few tasks in my life – the one that springs to mind at the moment is going to the airport. I’ve done this enough times to know that I need to leave my house two hours before take-off in order to be at the gate with a comfortable margin of safety.

Take Care of Things in Advance

Even though the prediction-improving techniques we’ve gone through above are quite useful, on of the best methods for making sure you’re never late is to simplify the process by doing things ahead of time.

If you can get half of a task done well ahead of when it needs to be done – or if you can take steps to make a process simpler every time it happens – then finishing the remaining steps will be much easier when it comes time to do them.

This is one of the reasons why business take the time to write out Standard Operating Procedures (SOP’s). They mainly exist to codify a process, which makes it much easier to train a new person on how to do it; however, the act of sitting down and writing down an SOP enables the writer to identify steps in the process that could be made more efficient – either by being done ahead of time, done in bulk, or removed altogether via automation, delegation, or elimination.

One of areas in your life where this technique might work best is your morning routine. Many people have trouble getting to work/school on time while also doing all the of the things they want to do in the morning. I was having this problem myself lately; I kept getting to skating practice late because my morning routine was inefficient.

So I decided to fix it. Here are a few of the things I’ve started doing:

- Bulk cooking – I cook a HUGE scramble full of eggs, sausage, potatoes, peppers, onions, and spinach a couple of times during the week. Each batch gives me three breakfasts, which I just warm up in the mornings. I also make sure to fill up the tea kettle before bed so I can just wake up and turn it on.

- Pre-packing – I make sure to pack both my work bag – computer, earbuds, current book, notebook – and gym bag – skates, water bottle, blade guards, etc – before I go to bed. Then I can just grab it in the morning

- Wardrobe prep – I lay out my workout clothes right next to my keys, wallet, and watch before bed as well

If you need to shave some minutes off your morning routine, give these a try! Though I will say that the likely culprit to your morning time crunch may be the snooze button – and if that’s true, you might also find my video on how to wake up early to be helpful:

On a related note, you’d also be well-served by adopting a habit of “clearing to neutral” – i.e. resetting everything back to its base position – either when you’re done with a task or at the end of the day. This means doing things like:

- Closing all your browser tabs and turning off your computer at the end of the day

- Cleaning up your workspace and room

- Washing all your dishes

When you clear to neutral, you eliminate a couple of extra threats to your punctuality:

- Losing things – when you clear to neutral, everything goes back to where it should be! No more lost keys in the morning; they go on the hook by your bed, right?

- Mental clutter – messy room, messy mind. When my room (or the kitchen) is a mess, it can cause distraction and decision fatigue. Do I take a few minutes to clean up these dishes, or leave them and feel bad?

For a more in-depth exploration of the Clear to Neutral concept, check out this article from my friends at Asian Efficiency.

Schedule an End Time for Your Current Task

When I was around 12 years old, I had a several week-long stint when I was absolutely addicted to a PS1 game called Yu-Gi-Oh! Forbidden Memories. I’d play it every night with my brother, until my mom would inevitably yell up at us that it was time to get ready for bed. I bet you can predict our response:

“Just five more minutes!”

And hey, I legitimately needed to beat Jono and get to a save point.

Of course, we wouldn’t just stop there. We’d keep pushing it and pushing it – five minutes at a time – until she’d finally come upstairs and make us turn off the PS1. We certainly weren’t happy about it, but her strictness was the only reason we ever got to bed on time.

Nowadays, my mom can’t make me go to bed on time because I’M AN ADULT.

In fact, my mom’s not around to make me do anything – which means I have to rely on self-discipline to make myself do things, such as stopping whatever I’m doing right now in order to move onto the next thing on the schedule. And that can be difficult.

How often do you find yourself running late because you wanted to “just finish up this one last thing?” Or because you just couldn’t stop dawdling or procrastinating?

Wait But Why illustrates this PERFECTLY: When the rational, decision-making part of your brain decides it’s time to start moving onto the next event, your brain’s Instant Gratification Monkey tends to say,

“Cool, but not THIS minute, the next minute!”

…and it, of course, keeps doing this for 20 minutes. At which point you have yourself a nice little panic attack.

Why does this happen so often? Well, to oversimplify the science a bit, there are two main parts of your brain that are involved in the decision-making process: your pre-frontal cortex and your limbic system.

These two parts of the brain usually work together quite well, but when you’re faced with a case of instant gratification vs. future-minded discipline, they’re at war. Your limbic system contains your brain’s reward center – the place where the dopamine flows when you’re doing something you enjoy (again, oversimplification).

When you’re caught up in a task you enjoy, or when you’re dawdling on Facebook, your limbic system is happy right where it is. And, unfortunately, it’s much older (evolutionarily speaking) than your PFC, which means it’s quite a bit stronger. Your PFC has its work cut out for it when it sets out to out-muscle the limbic system.

That’s why I recommend enlisting the help of an external system. If you want to make sure you stop your current task in time to move onto the next one, schedule an end time for it. Ideally, this end time would allow for a cool-down period before you need to start heading to your next event – remember the Planning Fallacy.

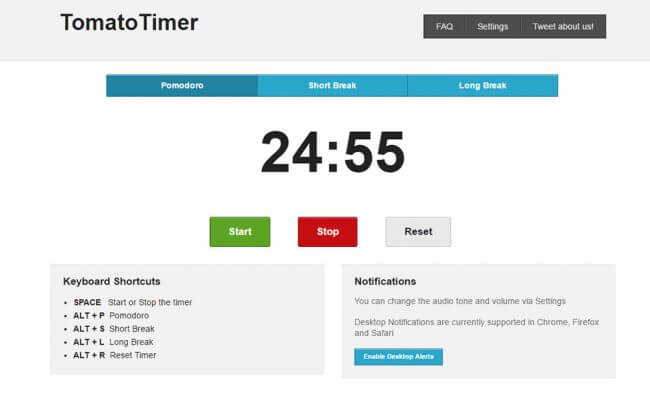

There are a couple ways you can do this. One option would be to work during a Pomodoro session – using a tool like Tomato Timer (the one I use) or even your phone timer – and to make sure the session ends right at the right time.

Another method would be to simply set an alarm on your phone, which will remind you to start wrapping up the thing you’re currently doing. Either way, using an external system will help reign in that rogue limbic system.

Use Your Calendar and Set Event Reminders

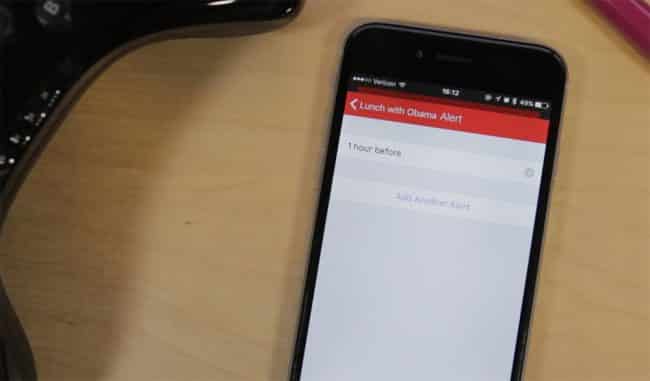

The last tip I’ve got for you today should help eliminate another problem that causes people to be late: forgetting events.

Sometimes you might forget an event altogether; other times, you’ll only remember it five minutes before it starts – when you’re across town and can’t possibly get to there in time. Queue the panic attack.

Fortunately, you can easily eliminate the problem of forgetting events by simply using your calendar the right way. You can click that link to see my full video on how I use my calendar, but it really comes down to three golden rules:

- Add events to your calendar the moment you learn about them.

- Check your calendar every day, right when you wake up (or at least during your morning routine).

- Use event reminders if you need them.

If you create daily task plans like I do, then you’ll naturally add whatever you find on your calendar to said plan as well.

Don’t ignore these three rules, even if you think you’ve got some kind of crazy genius brain that remembers every event on your schedule.

Even if you could remember events with 99% accuracy, your calendar will beat that by 1%. Besides, David Allen said it best:

Let your trustworthy systems do their job, and then point your brainpower at other problems – like which podcast you’ll listen to while you leisurely drive to your next event.

Take your time – you’re in no rush!

If you’re unable to see the video above, you can view it on YouTube.

Looking for More Study Tips?

If you enjoyed this article, you’ll also enjoy my free 100+ page book called 10 Steps to Earning Awesome Grades (While Studying Less).

The book covers topics like:

- Defeating procrastination

- Getting more out of your classes

- Taking great notes

- Reading your textbooks more efficiently

…and several more. It also has a lot of recommendations for tools and other resources that can make your studying easier.

If you’d like a free copy of the book, let me know where I should send it:

I’ll also keep you updated about new posts and videos that come out on this blog (they’ll be just as good as this one or better) 🙂

Video Notes

- Allocating time to future tasks: the effect of task segmentation on planning fallacy bias.

- Reference Class Forecasting

- The Planning Fallacy

- Steve Pavlina’s article on the Fudge Ratio concept

Have something to say? Discuss this episode in the community!

If you liked this video, subscribe on YouTube to stay updated and get notified when new ones are out!