So here’s a common scenario: You’re taking English 101 or “Freshman English,” or whatever your school calls it, and the professor gives you the following assignment:

“For next Friday, I’d like you to write a 1,000 word essay on one of the poems we’ve been studying. MLA format. Please use at least three secondary sources, one of which must be a print book.”

“Well shit,” you think. “How am I ever going to do that? 1,000 words! That’s like…4 pages double-spaced. And I hate MLA format. Too many stupid rules. And I have to use a book! Who even reads those any more?”

We’ve all had those moments, and especially if you’re in a STEM major (in which case you have my utmost respect), this sort of assignment can feel like a chore, besides seeming far too vague and open-ended.

Today, I hope to alleviate some of your confusion and anxiety. I can’t give you an exact formula for a perfect paper, but over the course of this post and its upcoming follow-up I’m going to walk you through the process I’ve used to get consistently high grades on my essays.

I’m using an English paper here as my example since that’s the topic I have the most experience with, but with a bit of adaptation you could apply this method to most other humanities essays you’d have to write.

Step 1: Close Reading

Before I can explain what close reading is, we need to choose a text to work with (a “text” is a term English majors use to refer to any written work they’re analyzing).

For our purposes, I’m going to use Emily Dickinson’s poem “Hope is the thing with feathers,” as it represents the level of poem you would deal with in a typical 100 level English course. Dickinson can be quite difficult to understand, but this poem is not too hard. A quote from it even appeared in one of my favorite Arthur episodes.

Here’s the text of the poem:

“Hope is the thing with feathers”

by Emily Dickinson“Hope” is the thing with feathers –

That perches in the soul –

And sings the tune without the words –

And never stops – at all –And sweetest – in the Gale – is heard –

And sore must be the storm –

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm –I’ve heard it in the chillest land –

And on the strangest Sea –

Yet – never – in Extremity,

It asked a crumb – of me.

The Reading Process

The first step to writing about the poem, obviously, is reading it – but not just like you would read a news article or a post from one of your favorite blogs.

This kind of reading is focused and attentive, hence the term “close” reading. You’re not just reading for information as you would when you read a textbook; rather, you’re trying to find a deeper meaning than the literal one on the surface.

Of course, that kind of understanding is the ultimate goal. To begin, it’s helpful just to read through the poem normally and try to understand what the author is describing. Once you have the surface meaning down, you can go back through and look for deeper meaning.

Let’s do this with the poem above. I’ll make some general observations, and then take it line by line. If I were doing this for a real essay, I would print the poem out and mark on it, but for the sake of legibility here I’ll type my notes.

I’ve numbered the lines for convenience, something you’ll need to do anyway when you write the formal essay since a poem has no page numbers.

1 “Hope” is the thing with feathers –

2 That perches in the soul –

3 And sings the tune without the words –

4 And never stops – at all –5 And sweetest – in the Gale – is heard –

6 And sore must be the storm –

7 That could abash the little Bird

8 That kept so many warm –9 I’ve heard it in the chillest land –

10 And on the strangest Sea –

11 Yet – never – in Extremity,

12 It asked a crumb – of me.

General observations: The poem is in three stanzas (groups of lines) of four lines each, for a total of twelve lines. It’s pretty short, in other words. Just skimming it, I notice a lot of dashes, which is unusual. I also see some quotation marks and capitalized words. I’ll examine those features more closely when I read line by line.

Line by line observations/questions

Line 1: A strange thing to say, but not hard to imagine. Hope has feathers, so maybe she’s comparing it to a bird. And why is “Hope” in quotation marks?

Line 2: Another strange image. How can hope “perch” in the soul? She still seems to be using this bird metaphor, though.

Line 3: Yep, she’s definitely comparing it to a bird, as it sings. And it makes sense that the tune would have no words, since birds don’t really talk.

Line 4: So whatever this “thing with feathers” is, it never stops. Never stops what? Singing, I suppose. I’ll come back to that.

Line 5: A new stanza here, which is important. It seems like she is still talking about the song here, since it “is heard.” But what does “sweetest – in the Gale?” mean? How can a song be heard sweetest in the Gale? I’m pretty sure a gale is an intense storm, but I’ll make a note to look it up later just to be certain (knowing the precise meanings of words is especially important in poetry, since a good poet makes every word count.) And why is “Gale” capitalized? It’s not someone’s name, but there must be some other reason.

Line 6: How can a storm be sore? That doesn’t make sense literally, so it must be a metaphor of some kind. I’ll look into that later. Also, is a storm different from a gale? How so? Is that important?

Line 7-8: (I’m taking these lines together since there’s no dash–the two lines are one complete thought): Okay, so now she clearly says that she’s talking about a bird. The previous lines make more sense now. But why is “Bird” capitalized? She did the same thing with “Gale.” What’s the deal with that? What does “abash” mean? I’m pretty sure it means “to make ashamed or embarrassed,” but I’ll look it up later just to be certain. And how does a bird, especially a “little” one, keep “so many” (I assume she means people) warm?

Line 9: Another stanza break here. I wonder why that is? She’s still talking about hearing this bird, but now it’s in “the chillest land.” What does that mean? Why is the land “chillest,” and why is it important that she heard the bird there, as opposed to somewhere else?

Line 10: Okay, so she also heard the bird/its song “on the strangest Sea.” What does that mean? Why there? I see that “Sea” is capitalized, just as “Bird” and “Gale” were. It must also be important. But why?

Line 11-12: To conclude the poem, the speaker says that the bird/hope never asked for even a little bit from her. What does “Extremity” mean? I think it means something like “the worst/most intense part or point of something,” but I’ll look it up to be sure. And it’s also capitalized, the fourth word in the poem to be like that. Why? Also, why is she talking about the bird asking for a crumb? Birds can’t actually ask for anything, at least not in words, and even if they could, why is that important? What does the “crumb” mean? Birds eat crumbs off the ground, so maybe it’s a pun of some kind. Still, why?

Whew!

I know that sounds like a lot of work, but when I actually go through the above process it takes maybe 15-20 minutes, and the notes I’m making are messier and not as detailed. Still, you get the idea.

One thing I want you to notice is that I asked a lot of questions, which will be useful in the research and writing phase, since an essay, in its most basic form, is a piece of writing that asks and answers a question or questions on a given topic. If you have questions in mind from the beginning of your reading, coming up with a specific paper topic and outline is much easier.

Also, notice that I made note of words I didn’t know. If you’re even sort of unsure of the meaning of the word, especially when reading a poem, underline it or mark it some way and then look it up and write the definition somewhere on the same page as the poem so that you can refer to it later (this is also just a good way to expand your vocabulary, an important part of learning new things).

The Next Step

Now that you’ve read the poem a couple times, you should come up with a general essay topic to guide your research (the process of finding the three sources your professor asked for).

It doesn’t have to be ground-breaking or eloquent, and it will likely change as you write the paper, but having something to work with will keep you from freaking out and becoming a caffeinated zombie stumbling through the library at 3am searching for last minute sources, only to collapse amid a pile of books.

The best way to create this “working thesis,” as we’ll call it, is to look back over your notes, pick something that stands out to you, and then write 1-2 sentences that describe that topic. I’ll explain this in more detail in the next post on Close Writing, so if you’re confused right now don’t worry.

Looking back at the poem and my notes, I’m going to focus on the prevalent image of the poem: the comparison of “Hope” to “the thing with feathers”/”bird.”

The essay will attempt to answer why Dickinson makes this comparison. I could get more detailed if I wanted to, but this is enough for me to go forward with research.

Research

Now that we have a general thesis to work with, let’s move to the research stage.

A lot of people have the wrong mindset when it comes to research. They view research as a way to find sources to tack onto the paper in order to fulfill a requirement, rather than a chance to discover new or interesting angles on your topic.

If nothing else, research makes the writing process easier by preventing you from being vague or making stuff up, as you have real evidence to back up your claims. It also helps when dealing with difficult or subjective questions, as you’re able to call upon the knowledge of everyone who’s ever thought and written about the topic to help you.

“Great,” you may say, “but how do I do that? How do I find these awesome, helpful sources?”

Well, you can begin where you probably spend most of your time anyway: the internet.

Hitting The Books

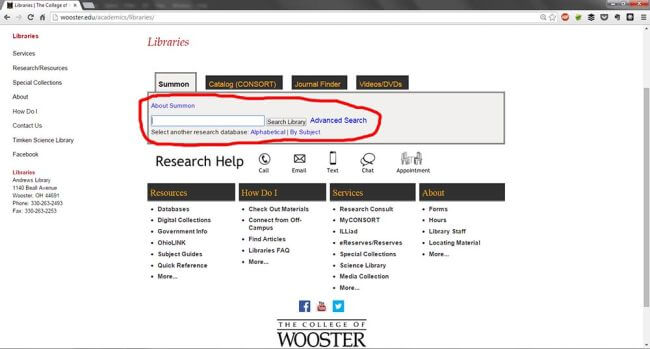

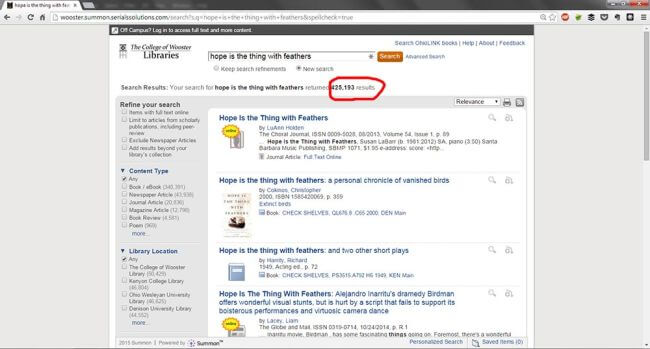

Since in our theoretical prompt the professor asked for one print source, the best place to start looking would be your school library’s database. For The College of Wooster, where I attend school, I would go to my school website’s homepage, click on where it says “Libraries,” and then enter some relevant search terms in the box.

The specifics of this may differ for your school, but I’m sure your librarian will be happy to help you if you’re not sure how to access this page.

I’ll start by typing in a general term related to the research at hand. Let’s try “hope is the thing with feathers.”

As you can see, this returns quite a few results, many of which are irrelevant to our topic.

Using the options in the left sidebar, I can refine the search a bit.

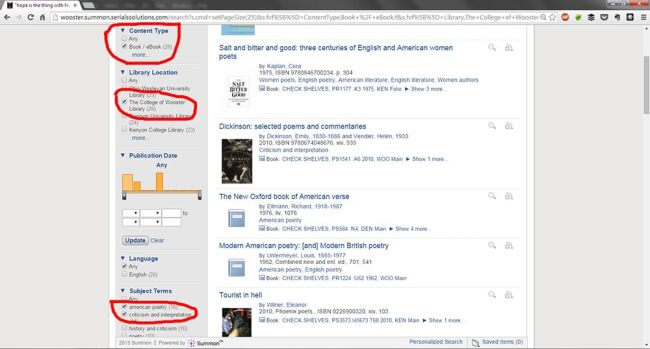

Let’s change the Content Type to “Book” (since that’s what the professor wanted) and the Location to “The College of Wooster Library” (since this theoretical paper is due in a week, I don’t have time to order a book from another library).

I’ve also refined the Subject Terms to “american poetry” and “criticism and interpretation” and placed the search terms in quotation marks to get rid of results that don’t include the exact phrase I’m interested in.

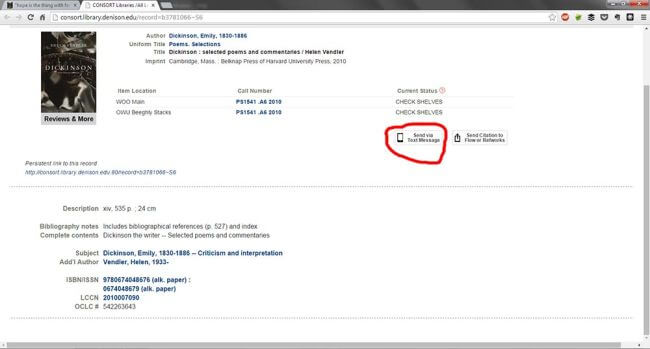

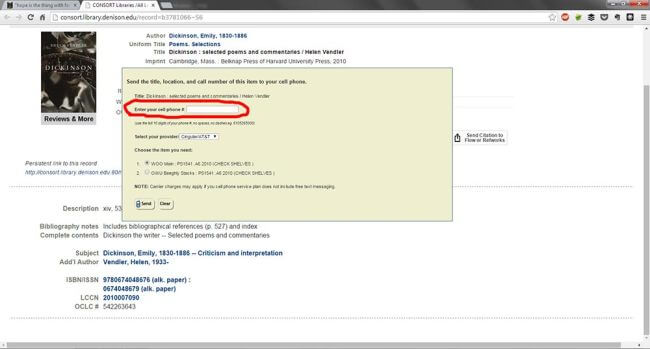

With these refinements, I find a book that looks promising. It’s titled Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries by Helen Vendler. I’d have to look inside the book to be certain it’s helpful, of course, but it’s a good place to start.

The next step, of course, would be to get the book from the library so that you can examine it. Depending on your library, you may be able to reserve the book and have them hold it for you at the circulation desk. You could also just go to the librarian and have them help you find it.

If you’re more of the DIY type like me, however, there’s another way to make finding the book easier.

My Favorite Library “Hack”

See where it says “Send via Text Message” on the book page? If I click that button and enter my phone number, I can have the call number for the book texted to me, which makes finding it much easier. It still requires a bit of hunting (which I admittedly enjoy), but it’s much easier than just wandering through the library at random.

Note from Tom: When I’m hunting down books in the library, I actually just pull out my phone and take a picture of the call number on the screen. Same concept!

Remaining Sources

Since I’m not at school as I write this, I can’t get ahold of this book and pull real examples from it for this post, but I hope you get the idea. Don’t worry, I’ll still show you how to quote and cite a print book using MLA format in the next post.

In the meantime, let’s find the other two sources your professor asked for. Although they don’t have to be print sources, I wouldn’t recommend just Googling “hope is the thing with feathers scholarly sources,” as you’re going to get a glut of irrelevant info. Check out the search results for yourself.

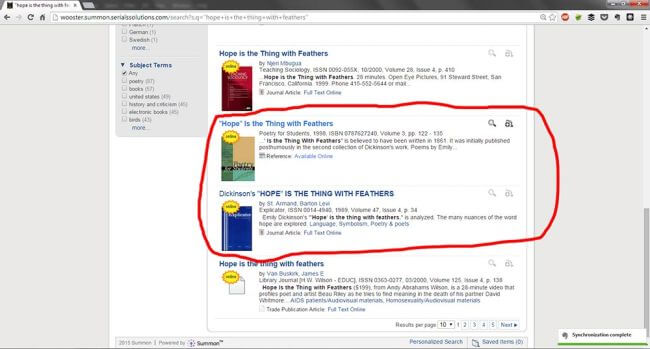

Rather, I would use your school’s library database to find further sources. Searching my school’s, I found an article in a journal called The Explicator that looks promising, as well as a book called Poetry for Students: Presenting Analysis, Context and Criticism on Commonly Studied Poetry by Marie Rose Napierkowski.

From this point forward, I’m going to assume that all three of these sources are relevant and helpful for our project, though with an actual paper you would want to skim through them and make sure that they work.

Final Steps

It’s also helpful at this point to make note of the relevant citation information for each source.

If using a book, note the exact title, publisher, publication year, and city of publication for your sources. If you’re using an anthology with an editor or editors, make note of their name or names as well.

If using any internet sources, make note of the author, article title, website title, date of access, and the last date the page was updated (if available).

If using a journal article, note the name of the journal, the volume and issue number, and the year of publication.

I’ll explain in the next post how to use this info to create a bibliography or works cited page, so don’t worry if you’re confused at this point.

You Did It!

Congratulations! You should now have a basic idea of how to come up with a paper topic and find sources to support it.

Once you’ve done those things, let’s move onto Part 2 – writing and editing your paper. In that article, I’ll explain in detail how to turn this work into an essay, taking you through the drafting process to the final polished paper.

Featured Image: Startup Stock Photos