Have you ever been taken advantage of? You probably have, without even knowing it.

In fact, I’d be willing to bet that if you’ve ever purchased anything, someone has at one point or another leveraged some psychological principle to get you to make the purchase “of your own free will.”

You shouldn’t feel bad. We’re hardwired to make automatic decisions based on limited information. It’s the only way to survive, particularly in today’s world.

As Robert Cialdini, author of Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, puts it:

“You and I exist in an extraordinarily complicated stimulus environment, easily the most rapidly moving and complex that has ever existed on this planet. To deal with it, we need shortcuts. We can’t be expected to recognize and analyze all the aspects in each person, event, and situation we encounter in even one day. We haven’t the time, energy, or capacity for it” (5).

In his book, Cialdini identifies six principles that drive our automatic decision making. The principles are as follows:

- Consistency

- Reciprocation

- Social Proof

- Authority

- Liking

- Scarcity

Ordinarily, these principles allow you to act automatically and efficiently in a way that benefits you. In certain situations, however, people with knowledge of these principles (Cialdini calls them “compliance professionals”) can exploit them to influence you to make purchases, donate money, or even torture people.

Don’t believe me? Come along and I’ll explain not only what the principles are, but also how to avoid being manipulated by them.

1. Consistency

“Foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.”

– Ralph Waldo Emerson

The principle of consistency states that we as humans have a need to make our actions line up with our stated intentions/beliefs.

As Cialdini puts it, “Once we have made a choice or taken a stand, we will encounter personal and interpersonal pressures to behave consistently with that commitment. Those pressures will cause us to respond in ways that justify our earlier decision.” (43).

Normally, this is good. A society where people were always inconsistent would be chaos, and cooperative endeavors would be impossible. It’s in everyone’s best interest to be consistent.

That is, unless, someone leverages that consistency for their own benefit. Cialdini gives the example of a classic sales tactic used by toy companies to increase their post-Christmas sales:

Leading up to Christmas, the companies market a particular toy to children, get their parents to agree to buy it, and then undersupply stores with the toy. This way, when it comes time for parents to buy the toy, they’ve already committed to their kids and have no choice but to go back and get the toy in January or February. The only alternative is disappointing their kids and being inconsistent.

I’d imagine that most of you reading don’t have kids, so let me give an example that’s probably a bit closer to home:

Many of you have probably stayed in an unhappy relationship or job just because you’ve made the commitment to it. Objectively, your situation is making your life very unpleasant, but yet you stick with it because to break from it means both admitting that you made the wrong choice and also appearing inconsistent. This situation is also an example of the sunk cost fallacy, which, combined with the principle of consistency, can lead to some pretty sorry situations.

So what exactly can you do to avoid falling victim to the pressures of misguided consistency?

Cialdini offers this advice:

“The only way out of the dilemma is to know when such consistency is likely to lead to a poor choice. There are certain signals— two separate kinds of signals, in fact— to tip us off. The first sort of signal is easy to recognize. It occurs right in the pit of our stomachs when we realize we are trapped into complying with a request we know we don’t want to perform” (80).

We’ve all felt it: that sinking feeling just like the one you get before the first big drop on a roller coaster…except that instead of signaling impending exhilaration, it’s a sign you’re about to be duped.

The second signal is a message from your “heart of hearts.” According to Cialdini, “Accumulating psychological evidence indicates that we experience our feelings toward something a split second before we can intellectualize about it” (84).

For those who don’t like the language of hearts, you might also call it a “gut feeling.”

Whatever you call it, the crucial move is that once you get these signals from your body, you should ask the following question: “Give what I know now, would I make this choice again?”

If this answer is “no,” then get yourself the hell out of there.

2. Reciprocation

“You scratch my back, and I’ll scratch yours.”

– American idiom

This principle is one so ingrained in our culture, we don’t even realize how pervasive it is.

The principle of reciprocation states that “we should try to repay, in kind, what another person has provided us” (13).

Reciprocation is so much a part of our culture that it has even influenced language. Phrases like “much obliged” have become synonymous with “Thank you” in English and other languages (13).

Again, this is normally advantageous. A system of accumulated gifts and obligations holds together societies. Reciprocation prevents people from cheating each other…usually.

Situations exist, though, when clever people exploit our tendency to reciprocate for their own profit.

For instance, have you ever walked into a grocery store and seen employees giving out free samples? This isn’t just to be nice–it’s solid business. By the principle of reciprocation, you will feel obligated to “repay” the store for the samples by buying the product you sampled. So think twice before taking that next free brownie.

As college students, we experience an even more specific brand of the “free sample” tactic all the time.

At least at my university, the campus is inundated the first week of fall semester with local companies pushing free samples of everything from school supplies to pizza.

The technical business term for this is “building brand awareness,” but you better believe these companies are also trying to get you to reciprocate their generosity with future purchases. And if they can get you to use their products consistently…you can see where this is going.

How the heck do you keep from getting bamboozled?

This one is especially tricky, since there are people with altruistic motives who really just want to give and expect nothing in return. Blanketly refusing everyone who tries to do you a favor or give you a gift is an easy recipe for looking like a jerk.

The key is to consider the person giving the gift, the situation you’re in, and the person’s potential motives. If you’re in any setting where purchases are expected (basically any business/store) or if the person doing the favor follows it up with a request for money. you should have no qualms about refusing:

“As long as we perceive and define [the person’s] action as a compliance device instead of a favor, [the person] no longer has the reciprocation rule as an ally: The rule says that favors are to be met with favors; it does not require that tricks be met with favors” (39).

If someone’s just being nice, then let them and be grateful. But if they’re trying to manipulate you, you owe them nothing but an emphatic, “No, thanks!”

3. Social Proof

“If all of your friends jumped off a bridge, would you?”

– Everyone’s mom ever

Life is complicated. Just think about all the social situations you encounter every day. We’re constantly thrown into new environments where we’re not sure how to behave.

This is where social proof comes to the rescue.

The principle of social proof states that in situations where the right action is unclear, we decide what to do by taking cues from other people: “In general, when we are unsure of ourselves, when the situation is unclear or ambiguous, when uncertainty reigns, we are most likely to look to and accept the actions of others as correct” (98).

Normally this is very helpful–it’s only by observing the actions of others that we can know how to behave in unfamiliar social situations. If we didn’t follow this principle, we’d end up making a lot of social faux pas.

More than any of the principles discussed so far, however, this one can backfire in some truly horrible ways.

Cialdini gives the example of someone having a heart attack in a crowded public place. You would think that this would be one of the best places to have a heart attack–there are so many people around that someone’s bound to help you. It turns out, though, that just the opposite is true.

What often happens is that everyone will just stand there waiting for someone to do something. Because this is an unfamiliar situation, the bystanders look to everyone else for cues for how to behave, but since no one is sure what to do, it creates a feedback loop of inaction.

Marketers/salespeople also take advantage of this principle in more innocuous ways all the time. If you’ve ever seen an ad with testimonials or endorsements from “average people just like you,” then you’ve observed an attempt to exploit social proof to sell products.

To be fair, there’s nothing wrong with actual testimonials, but all too often commercials will employ paid actors pretending to be “average people on the street.” While not technically lying (there’s usually fine print identifying the people as actors), it is dishonest in the way it exploits spurious social proof.

How to avoid the negative effects of this principle depends on the situation. In cases such as advertising, all you have to do is ask yourself whether the “average people” are real customers or just paid actors (and it’s often as easy as reading the fine print).

But what about in more serious situations such as the case of the person having a heart attack? What if you’re the one having a medical emergency in a crowded public area?

The key, according to Cialdini, is to remove the ambiguity from the situation. If you’re having a medical emergency, point at someone specific and say, “You there! I’m having [NAME OF MEDICAL EMERGENCY]. Call an ambulance” (118).

Don’t worry about seeming rude–in these situations it’s crucial to be direct, or else you risk social proof working against you. It’s also essential that you single out one individual. Simply saying, “Someone call an ambulance!” leaves the situation too ambiguous.

“If we can become sensitive to situations where the social-proof automatic pilot is working with inaccurate information, we can disengage the mechanism and grasp the controls when we need to” (118).

4. Authority

Han Solo: Look, Your Worshipfulness, let’s get one thing straight. I take orders from just one person: me.

Princess Leia: It’s a wonder you’re still alive.

– Star Wars: Episode IV: A New Hope

Popular culture is largely contemptuous of authority, but obedience to authority is something that is ingrained in us from infancy. As helpless babies, we have no choice but to submit to our parents’ authority. And even as we grow older and more cognizant, it makes sense to defer to our parents’ better judgment. For the most part, obeying them keeps us alive.

Furthermore, the benefits of obeying authority extend beyond family structures and into the broader world:

“A multilayered and widely accepted system of authority confers an immense advantage upon a society. It allows the development of sophisticated structures for resource production, trade, defense, expansion, and social control that would otherwise be impossible. The other alternative, anarchy, is a state that is hardly known for its beneficial effects on cultural groups and one that the social philosopher Thomas Hobbes assures us would render life “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short'” (162).

Even in everyday life, we regularly trust authorities to do things beyond our knowledge or ability. You wouldn’t try to do your own brain surgery (assuming that were even possible), and you probably wouldn’t try to argue your own case in court.

Trusting authorities, in sum, is usually the way to go.

The problem, though, is that it’s very easy to “seem” like an expert/authority without actually being one. Whether through fake titles, professional uniforms, or just an authoritative voice and manner, compliance professionals can easily simulate authority in order to get us to agree to their requests.

Cialdini gives the example of an experiment in which a man jaywalked across a busy intersection. In half of the cases the man was wearing casual clothes, and in the other, he was wearing a business suit. In cases where the man was wearing a suit, 3.5 times more people followed him across the street compared to when he was wearing casual clothes (170).

This experiment shows how easy it is to equate seeming with being.

If you’d like another, even more disturbing, example of the powers of authority, check out the infamous Milgram experiment.

As with the other principles, you neglect the principle of authority at your peril. You can’t doubt every single instruction your doctor gives or every piece of counsel from your lawyer. You likely wouldn’t survive long with this attitude.

Luckily, Cialdini offers two simple questions you can ask to decide if someone is using the authority principle to manipulate you:

- Is this authority truly an expert? (172)

- How truthful can we expect the expert to be here? (174)

If the answers to both are in the affirmative, then rest easy. If not, then get like Millennium Falcon and make for warp speed.

5. Liking

“I can tell that we are gonna be friends.”

– The White Stripes

The principle of liking states that we tend to cooperate with people we like, and, furthermore, we tend to like people who seem similar to us (131).

“Well, of course,” you might say. “Why would I help someone I hate?”

Like all the principles discussed so far, this one seems obvious. And again, it makes sense on the face of it. If someone is behaving in a friendly, likable way, that probably means they aren’t about to attack or cheat you. Probably.

This mental shortcut can easily lead us astray, though, because the reasons we have for liking people can be quite arbitrary and misguided. It turns out that it doesn’t take much for a person to get us to like them–a friendly smile and a few compliments are usually all it takes (and bonus points if they have/claim to have something in common with us).

The classic example of this is the used car salesman. A few jokes, a smile, a remark about how, wouldn’t you know it, the salesman also has a brother living in Iowa, and before you know it, you’ve driven off the lot paying far more than you ever intended. (On that note, Tom’s podcast on how to buy a car might be helpful to you)

And the used car salesman is just one example. Savvy salespeople across a whole host of businesses are likely to employ this tactic, since it requires little effort and gets big results.

To avoid the influence of unwarranted liking, Cialdini recommends the following strategy:

“Our vigilance should be directed not toward the things that may produce undue liking for a compliance practitioner, but toward the fact that undue liking has been produced. The time to react protectively is when we feel ourselves liking the practitioner more than we should under the circumstances” (153).

So basically, if you’re in a situation where you find yourself liking someone who’s trying to sell you something (and it could just as easily be an idea/ideology as a product), alarm bells should go off in your head.

Remember that the person selling you something doesn’t have your best interests in mind if they’re trying to manipulate you into thinking they’re your friend.

6. Scarcity

“For the vast majority of world history, human life – both culture and biology – was shaped by scarcity. Food, clothing, shelter, tools, and pretty much everything else had to be farmed or fabricated, at a very high cost in time and energy.”

– Martha Beck

“LIMITED TIME OFFER!!!”

“GET IT NOW BEFORE IT’S GONE!!!”

“ONLY 1 LEFT IN STOCK!!!”

These phrases are all attempts to leverage the principle of scarcity, which states that we see scarce things as more valuable than abundant things (179).

Historically, this made sense, because in prehistoric/ancient times scarcities were very real (and, in fairness, are still very real for many people around the world).

For many of us, however, true scarcity of essential resources is no longer a concern. This hasn’t stopped clever advertisers from exploiting our aversion to scarcity, however. The phrases above give us very general examples of how this principle works, but let’s get a bit more specific.

My favorite example of the scarcity principle at work is the online auction. I don’t bid on items online much, but from what experience I have, I know that it’s very easy to fall into the trap of bidding an item up not simply because I want it, but because I’m competing with someone else for it.

According to Cialdini, the combination of competition and scarcity can take our desire for something from strong to intense:

“Not only do we want the same item more when it is scarce, we want it most when we are in competition for it” (197).

In the wrong situations, this can drive us to spend irresponsible amounts of money on objects that have very little utility to us. It’s crucial, therefore that we learn how to avoid the manipulative influence of this principle.

Cialdini proposes a two-stage response to scarcity pressures:

- Notice the signs of a scarcity response. These include strong emotional arousal, increased heart rate, and a general feeling of being “on edge.” Once you’re aware that you’re reacting emotionally, calm yourself down by taking a few deep breaths (226).

- Once you’ve calmed yourself down, decide whether you want the scarce item because of its rarity or because of its function. If you want it because it is rare, that’s fine: just recognize that fact and decide how much you’re willing to spend for it. If you want it purely for its function, however, recall that the scarcity of an item will not improve its function (226).

Just remember: a $1 bottle of water from the gas station will quench your thirst just as well as this $100k one.

Conclusion

“Today, the notion that one of us could be aware of all known facts is only laughable. After eons of slow accumulation, human knowledge has snowballed into an era of momentum-fed, multiplicative, monstrous expansion….Novelty, transience, diversity, and acceleration are acknowledged as prime descriptors of civilized existence” (207-208).

I hope that after reading this article you feel just a little bit wiser about the workings of the world. I know that for me, learning about the actions of these principles was a mini “Matrix-revealed” moment–so much of life took on a new light.

Even if you didn’t find it that revelatory, I hope it will at least keep you from getting ripped off by a sleazy car salesman.

For your reference, here’s a list of the principles with a summary of each:

- Consistency – We want our actions to line up with our statements/beliefs.

- Reciprocation – If someone does us a favor, we feel the need to pay them back.

- Social Proof – In situations where the correct action is unclear, we look to other people for cues.

- Authority – We tend to trust and follow those with more experience/knowledge.

- Liking – We tend to help people we like.

- Scarcity – Scarce things seem more valuable to us than abundant things.

If I could sum up the lesson of this book in one sentence, it would be this: Be vigilant. If you maintain your situational awareness, you’re far less likely to let others manipulate you.

Relying too much on the internet for answers can make you much easier to manipulate. Here’s how to avoid that.

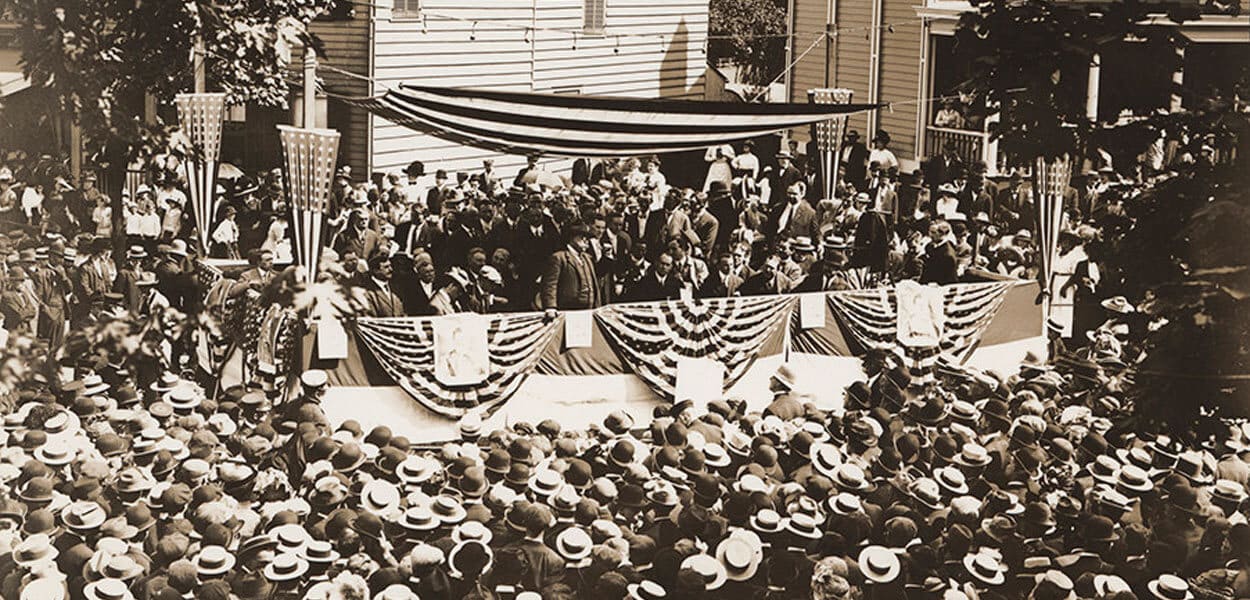

Images: surfer, gift, suit, smiling man, newspaper, grill, crowd.