I’m going to manufacture a big, scary-ass dude for you to ponder right now. I need you to help me out by imagining him along with me.

His name is Lennie, and he’s a solid 6’5″, 270lb. of bricks, nails, and other things you’re not supposed to eat for breakfast. Lennie is a one-man goon squad. What he is not, is a man to be trifled with.

On the 31st of the month, Lennie is going to find you, grab you by your ankles, and shake $298 out of your pockets. Nothing personal, but it’s going to happen.

Oh, and he’s going to keep doing that every month for the next 10 years.

Yeeeeeeah.

Alright, you can stop testing the absorptive capacity of your underwear now. Lennie doesn’t exist.

Unfortunately, there’s still a very high chance that, minus the ankle-grabbing bit, this monthly shakedown is still going to happen to you.

Want to avoid it? Then keep reading.

Lennie is Your Loan

I lied; Lennie does exist. If you have student loans, that is.

According to CNN, the average college graduate in 2013 is leaving school with around $29,400 in student loan debt.

Now, when you’re a high school senior who’s just been accepted to the college of his dreams, that figure doesn’t faze you. $30K won’t make you break a sweat when you’re a high-earning college grad with a great job, right?

I know this is what I thought. Luckily, I screwed my head on straight before it hurt me. But I also know this is the common wisdom most future college students hear. Stuff like:

“Student loans are an investment in yourself. You’ll be able to easily pay them off with the higher earnings you’ll receive thanks to your degree.” – role models stuck in the past

Listen, friend. Please listen. Student loans are debt. Don’t let someone candy-coat it. They are debt, and they represent a burden you will have to carry if you take them.

The point of this article is to accurately illustrate how loans are likely to affect you once you graduate. I believe that most students aren’t educated on this subject – far too often, their loan amount is overshadowed by the non-specific (and uncertain) expectation of “making enough in the future for it”.

This is done whether a student is taking out $15,000 or $80,000. Even though these amounts are vastly different, many students would put no further thought into taking the latter then they would for the former.

This is scope insensitivity at its worst, and I’m here to destroy that. Let’s pull the veil up here – behind all the expectations of great results, loans represent a concrete and specific burden.

Standard, Average Lennie

Let’s take that average debt load – $29,400 – and figure out just what that translates to in terms of the burden it will represent when you graduate.

Currently, undergraduate students can borrow up to $27,000 in federal Stafford loans – $5,500 during freshman year, $6,500 for sophomore year, and $7,500 for junior year and each year after. This is assuming you graduate in four years.

The current interest rate on Stafford loans is 3.86%, thanks to Bipartisan Student Loan Certain Act of 2013, which Obama signed on August 9, 2013. This rate is incredibly low compared to private loan options, but it’s still interest.

Stafford loans have a standard repayment term of 10 years.

So here’s information we’ve currently got:

- $27,000 loan balance

- 3.86% interest

- 10 years to repay

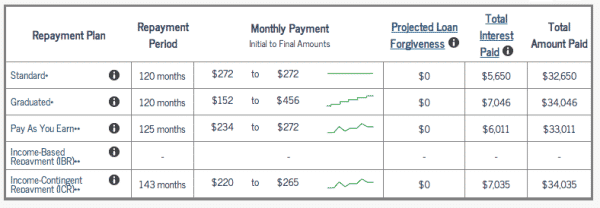

Using the government’s handy loan repayment calculator, I came up with this repayment table:

Notice that there are other repayment options; however, for the purposes of this example, we’re going with the Standard repayment option.

So we’ve ended up with a figure of $272. That’s your monthly payment for the Stafford Loans. Now, if you qualified for some subsidized loans, then some of your interest won’t start accruing until six months after graduation – but even so, the figure won’t change that much.

But wait. Wasn’t the average debt load $29,400? Looks like we’re missing some money here.

To make up the difference, I did a search on AllTuition for a private loan in my area. (This is not an endorsement for taking private loans! Read on for my opinion on them a little later)

Here’s what I found:

- Loan Amount: $2,400

- Repayment Term: 10 years

- Interest Rate: 6% (this is a general estimate taken from the several loans I found)

- Monthly Payment: $26

So if we add that $26 monthly payment to our previous figure of $272/mo from the Stafford loans, we end up with the final amount – $298.

This means that if you’re in this situation – that is, if you’re the average student – then Lennie will be shaking you down for $298 per month for 10 years after graduation.

At this point, I’m going to ask you a favor:

If you know a high schooler who’s planning on going to college soon, please send them this article.

Students deserve to be educated on the real burdens of student debt, and they should know about it before they actually take our loans.

“Lennie’s a small-fry. I’ll easily earn enough to pay that off, right?”

Once again, this is the typical “wisdom” that’s thrown around by teachers, parents, and various other adults. To be fair, this line of thinking wasn’t so far from the truth at one point in time.

According to this 2006 CNN article, only 46% of college students took out loans in 1990 – and their average debt load was around $6,800 at graduation (about $12,100 in today’s dollars).

That’s a far cry from $30k – and while median household income has increased since then, it certainly hasn’t doubled.

It’s not as easy to pay off student loans today as it once was, and they now represent a much more significant burden.

Let’s continue with our “average graduate” case and look at the burden this $298/month loan payment affects you. According to NACE, the average starting salary for a college graduate in 2013 is $45,327.

(Social science, English, and design majors are welcome to leave a sarcastic comment about this figure now)

Keeping in mind that this is the average, and that your choice of major could put your starting salary at a point far below this, let’s crunch the numbers.

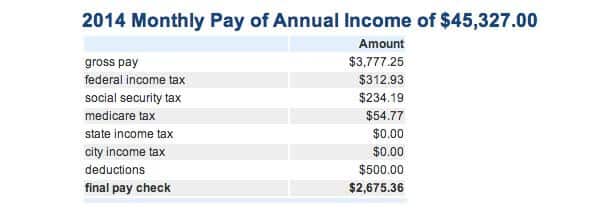

Using this take-home pay calculator, I ended up with this monthly net pay figure:

A grand total of $2,675 per month. This is assuming a $500/mo 401K deduction, which was the default setting on the calculator.

Before I start breaking down exactly where this money is likely to go, I want to point out an interesting fact you probably don’t see thrown around much.

In chapter 2 of Zac Bissonnette’s excellent book Debt-Free U (which happens to be #1 on my list of essential books for students), he cites a 2002 Nellie Mae study on the impact of student debt related to income.

Here’s what was found:

- Borrowers who required less than 7% of their gross monthly income to repay loans generally do not feel difficulty.

- The “perception of difficulty” is “somewhat amplified” when the percentage is between 7%-11%.

- After 11%, repaying the debt starts to become highly stressful and difficult.

Our gross monthly income in this example is $3,777, putting a $298/mo loan payment squarely at 7.9%. Fortunately, this is on the lower end of our “somewhat difficult” spectrum, but it’s still past 7%.

$3,479 Leftover is More Than Enough, Right?

I’m not delusional, so I know that it’s unlikely to move a high-schooler if I tell them that some dumb survey said a measly 7.9% of their income going to loans would be seen as difficult.

High-schoolers can do some amounts of math, so they’re likely to realize that still leaves them with 92.1% of their income – $3,479. That’s more than enough to live comfortably and buy whatever you want, right?

Well, maybe. But let’s do the actual math. Remember, the point here is to illustrate the actual burden.

First off, you’re not going to see that whole $3,479 each month. Taxes, dummy. Refer to the take-home pay graphic I posted above – in this “average grad” example, you’re taking home just $2,675/mo.

It’ll probably be less, actually, since most companies will withhold more than you actually owe for taxes each month.

Yes, this means you’ll likely end up with a nice return each year – but most people aren’t disciplined enough to save it all and split it between their next 12 monthly budgets. Can you tell me with a straight face that you’re not buying a PS4 with some of that money?

But to humor you, we’re sticking with that number. Now let’s see how far it goes.

For this example, let’s assume you’ve landed that nice $45k/yr job in Milwaukee, WI. I’ve chosen this city because it has a pretty near-average composite cost of living index, so it seems like a good choice.

So you’re moving to Milwaukee, which means that – at least for now – you’re going to find a single-bedroom apartment and live on your own.

Using this as a springboard, let’s see what your typical monthly expenses might be (data obtained here, mostly):

- Rent: $600 (assuming you’ll commute a bit)

- Utilities: $133

- Internet: $40

- Cell Phone: $40

- Auto: $350 (gas, car payment, insurance)

- Groceries: $230 (low-cost plan)

- Entertainment/Misc: $150

In total, your expenses with this budget are $1,503/mo. Which means:

- With your $298/mo loan payment, you’re left with $874/mo.

- Without that loan payment, you’d have $1,172/mo.

“Hey, wait a minute – this doesn’t seem too bad!” – you, possibly

In all reality, no it doesn’t. Having $874 left over every month seems pretty good.

Now, this budget doesn’t take into account other expenses that could come up – having a kid, being forced to pay for your own health insurance, etc. But still – you’re looking pretty good in this scenario.

A Slightly Bleaker Scenario

Remember, the case we went through above was using all the averages. That average starting salary? That’s the average of all majors.

While the outcome in that example looked pretty good, I want to show you what can happen if just one variable is changed.

Now let’s assume you’re graduating with the standard amount of debt – $29,400 – however, you majored in English and managed to score a job at a $35k/yr salary.

Here’s the picture you’re looking at now:

- Take-Home Pay: $1,999

- Expenses: $1,503

Before your loan payment, you’re left with $496/mo. That’s quite a bit less.

On a Standard loan repayment schedule, you’d be left with just $198 each month.

You may be able to lessen the load using a different repayment schedule; using the calculator, I found that the “Pay as You Earn” plan for Stafford Loans would bring the monthly payment down to $148 at first.

Under that plan, you’d be left with $348/mo after all your expenses.

As long as you were responsible with your money, this would still be an ok situation. Things are getting a bit tighter now, but you’re still keeping a good chunk of change each month that you can start saving or investing.

The Much Bleaker Scenario

So far, our example cases have used mainly federal loans – meaning that easier repayment options are available, and interest rates are pretty low.

What happens, though, when someone takes out a bunch of private loans to finance their education?

What if, say, a student takes out $50,000 at 6% interest to go major in journalism at an out-of-state private school?

If he ends up making that same $35k the English major made, things start getting pretty bleak indeed. Even if we bump up the repayment term to 15 years, he’s still paying $421/mo on that loan…

…which leaves him with just $75/mo after expenses. That’s not much to save, and it’s not much to have lying around if something goes wrong (hint: things go wrong in life).

This is why I’m so adamant about educating people on the true burden of student loans. I don’t want to see anyone in this scenario, yet thousands and thousands of college grads are already living it – or something even worse.

Just read any of these articles if you want proof:

- 7 College Graduates Whose Lives Were Wrecked by Student Loan Debt

- Student Loan Horror Stories

- Millenials’ Ball-and-Chain: Student Loan Debt

When I see quotes like this, I know there’s a problem:

“I really had no idea of the true cost of college. I just signed what I needed to sign and had no idea how much in loans I was taking out.”

Hopefully this article will help – in whatever small way – to fix it.

What to Do Now

This article is pushing 2,200 words already, so I’m not going to get into a ton of specific advice on how to go to college without taking loans. I will cover that topic in another article soon, though.

For now, this is what I want to leave you with.

1.) You can’t buy a great future. You do not have to attend an Ivy League or some prestigious private school to get a great job in the future. Your prospects are much more dependent on the work you put in.

That work can easily be put in at an in-state college that won’t cost you an arm and a leg. Honestly, you’re probably better off going to a state school anyway; they’ve got a lot more resources for you to use, and less super-star professors who’d rather publish research than actually teach you.

2.) NEVER take a private loan. I’m just going to quote Zac Bissonnette here to hopefully drill it in:

“Neither you no your child should ever, under any circumstances, ever, take out any private student loans.” – page 80, Debt-Free U

Seriously, don’t do it. There are a ton of education options that are affordable, so if the one you’re looking at isn’t attainable through some combination of scholarships, grants, work-study aid, federal loans, and your own savings, then it’s too expensive.

3.) Do the fucking math. Never let me catch you saying “I didn’t know the true cost of college.” I will poop right on your car windshield.

If you think you’re smart enough to go to college, then you’re smart enough to do the research necessary to know how much your education will cost you and how it will affect you after graduation.

Do your research. Ask questions and don’t take things at face value. Don’t let motivational talk and hope replace hard numbers and statistics. Use the calculators and websites I’ve linked to in this article.

Your future is up to you. Be mindful of your path, and make sure you’re not biting off more than you can chew in the future.

Otherwise, Lennie’s gonna mess you up.