Budgeting, as a concept, is very simple. You manage inputs and outputs, hopefully keeping the latter higher than the former.

If you’re anything like me, you learned the basics of budgeting when you were 10 years old by playing Age of Empires II. You had to manage the production of resources – wood, food, gold, and stone – in order to build new facilities, research technologies, and advance through the ages.

Eventually, you just typed in the cheat code for the red sports car with laser cannons and tore the Celts a new one. But, and it pains me to say this, there are no laser-shooting sports car cheats in real life.

In this life, budgeting is even more important. The lack of cheat codes and the general importance of having enough money to eat mean you need to have a little bit of budgeting competence. If you want to actually graduate from college and end up debt-free, well, you’ll need to know a bit more.

Today, I’ll impart my thoughts and experience in the realm of budgeting with an emphasis on doing it in college. As a student, you’ve got to deal with several factors that don’t come up in other stages of life – and you’ve generally got pretty small coffers to boot.

Do You Even Need to “Budget?”

Let’s put something straight here. If you look at my other “Ultimate Guide”-style posts – the one on how to build a personal website, for example – you’ll notice that this one, though lengthy, is still decidedly shorter. Why?

Well, to be honest, I don’t really want you to have to put a whole ton of thought into budgeting. It should be simple and, after some initial setup, it should become little more than a background process in your head. It shouldn’t be an item of too much concern once you’ve structure everything correctly and fixed your spending habits.

Think of your mind’s ideal picture of “budgeting.” What comes up? Do you think of the financially savvy member of the household sitting at the table every month, writing down spending caps in all the family’s different expense categories and minutely balancing available funds?

This, my friend, is called micromanaging. It’s something you probably don’t want to be doing with your time. And, incidentally, it’s something the best budgeters actually don’t do.

Here’s an excerpt from Jeff Yeager’s book The Cheapskate Next Door:

“Contrary to what non-cheapskates seem to think, only about 10% of the cheapskates polled said that they have a formal, written household budget. For most of us, a budget seems too much like a diet: a plan that’s always looming over you, bring you down, when what you really need is a lasting lifestyle change that makes the desired behavior effortless.”

This, ladies and gentlemen, is why I’m such a geek for Habitica.

Habits + well-defined goals > micromanaging. This is true for studying, it’s true for dieting and exercising, and it’s true for budgeting.

So let’s dive into this purposely brief (for my standards, at least) guide by starting out with those all-important goals!

Define Your Financial Goals

Let’s talk about tactics and strategy for a second. When I was taking an intro-level business class early on in college, the professor defined three levels of management that make up classic corporate structures (wow, that’s a boring string of words…):

- Strategic management

- Tactical management

- Operations management

This is actually a good way to think about your financial life as well – like a business, you’ve got income, expenses, and (hopefully) goals. You don’t have interns to fetch you coffee every 15 minutes or a crack team of elite hackers to do your espionage dirty work, but we’ll deal with what we’ve got.

Strategic management is concerned with the big questions that steer the entire company. Where do we want to go? Where are we now? What value do we have? Your strategy defines your direction, and it is the basis for all the smaller decisions that come after it.

Tactical management, on the other hand, concerns itself with how the strategic goals will be achieved. What systems should we build? What choices should we make for individual decisions? As these decisions are made, operational management ensures the day-to-day workings of the business run smoothly and stay in line with the strategy and tactics.

So let’s put this in terms of your own life:

- Strategy: Your financial goals, your current situation, and your overall money philosophy

- Tactics: The systems you set up to deal with regular money flow and your individual financial decisions

- Operations: Your day-to-day money details – here we’re largely concerned with your spending habits

To do well in the tactical and operational areas, you first need a solid strategy – a financial goal.

If you take a look at the Life section of my Impossible List, you’ll see that I have a very well-defined goal for my own finances.

By the time I (along with my girlfriend Anna) turn 40, I want to have $900,000 invested. At that point, I’ll be able to effectively retire early. I’d like to live on 4% of that – $36,000/year – and even based on an extremely conservative estimated return of 5% per year, the money would never run out. More likely, the return would be more around 7% at least.

This isn’t to say I want to stop working at 40; creating things brings me far too much joy for that. I’ll probably never stop working. However, I do want to detach my need to work from my need to pay for my existence. My goal is to build a system that guarantees my existence at my desired (sane) standard of living, no matter what I do after that. From there, I’d be free to pursue any project I’d like, regardless of its profitability.

Based on that goal, we need to save about $25k/year. Now, this is a bit simplified – if I want to adjust that $900k figure to account for inflation, I’ll need to adjust the yearly investment as well. Still, it gives me direction that I can apply to the tactical decisions. Knowing how much I need to invest per year, some simple math will tell me how much needs to be socked away each month.

“But that goal is crazy!” – you might say

Here’s the thing about my goal: It fits my current situation. At this stage, I’ve graduated from college, I have no debt, and my business is growing. I make a good income and can reasonably expect to meet my saving goals if I’m smart about my spending.

Two years ago, this wasn’t my situation. I was still in college, I had ~$14,000 in student loans, and I didn’t make nearly as much money. At that time, my financial goal was much different:

- Make enough money each month to cover my expenses (and have some for emergencies)

- Destroy my student loans – before graduating

This was a very different goal – but it was still well-defined based on my situation. Since it gave me clear direction, I paid off all my student debt before my graduation deadline.

So here’s your mission at this stage:

Sit down and create a financial strategy. Set goals that make sense based on what you want out of life and what your current situation is. Be optimistic, but also realistic. Doing this will help you create the systems that’ll start moving you forward.

Do a Financial SWOT Test

Going back to our business analogy. Another oh-so-exciting term we learned about in business class was how to perform a SWOT analysis, which looks at:

- Strengths

- Weaknesses

- Opportunities

- Threats

Guess what – you can (and should) do this too! But let’s modify it a bit: Instead of SWOT, your personal analysis of your finances gets the decidedly less-memorable acronym IEOT. Don’t ask me how to pronounce that.

IEOT stands for:

- Income

- Expenses

- Opportunities

- Threats

…so it’s not much different from SWOT.

Take a bit of time and assess your own situation in each of these areas. How much do you currently make each month? Is that income stable? (Mine fluctuates) How much do you spend each month – and how much of that is essential?

For opportunities, think about the probability that your income could increase in the near future. Do the same for threats – think ahead and assess any potential big expenditures that might be coming your way.

One exercise I recommend doing here is getting your “number.” By that, I mean the number of dollars you have to spend each month. Before I was a co-host, my friends at Listen Money Matters did an episode on this concept, on which I actually left a comment defining my own number. Here are my stats:

- Rent: $305

- Utilities: $75

- Phone: $85

- Car insurance: $15

- Groceries: $200

- My “number”: $680

Living in the middle of Iowa with three roommates, my number is exceptionally low. It doesn’t include my business expenses, and it’s certainly nowhere near what I actually spend, but this the bare minimum I need to make to keep myself alive in my current situation.

It would mean canceling all my subscriptions to things like Spotify, taking the bus or my bike everywhere, and being very frugal on food, but I could do it.

Pretty low, right? Your number may be higher or lower, but either way, it’s good to know it. It’ll be integral to the next step.

The goal here is to be aware of where you are instead of lost. When you’ve got this step on lock, move onto the next one.

Create a Money Pipeline

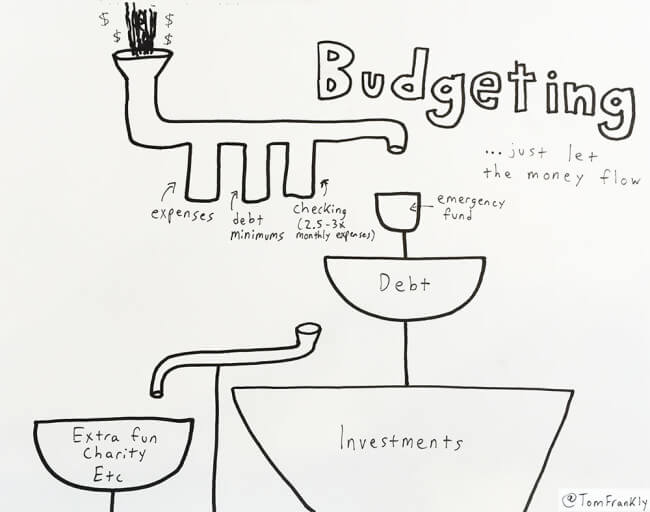

I have a brain that likes to visualize a lot and create analogies for everything. To that end, I think of money management in terms of water flowing through a pipe system.

The main reason I use this analogy is because I want to create a system that tells me where my money should go. I’m well aware that human willpower is limited, even when we build strong habits, so externalizing as much of the process as possible is a smart thing to do.

My goal: Build the system, then let it do its work and keep an eye on it.

So here’s my money pipeline:

At the top, we’ve got income flowing in. The way the pipeline is designed, the most important areas get filled first before the money can flow to the next area. So, when money comes in, we take care of (in order):

- Monthly fixed expenses – rent, utilities, bills

- Debt minimums

- Fill the checking account (more on this in a bit)

- Fill a separate “emergency fund”

- Take down debt

- Invest most of what’s left, but let a little go to fun, charity, etc.

Now, the biggest thing to keep in mind is that this is a conceptual pipeline. It does not represent the order of actual payments you’ll make.

Take your debt, for instance. You won’t make a minimum payment, then fill your checking account, then make an additional payment. Rather, you’ll use the pipeline as a planning tool when income hits your bank account. An example thought process:

“I owe at least $50 on my student loan, and I need to put $800 into checking to keep it at my desired level. I’ve got $2,000 left after fixed expenses, though, and my emergency fund is filled. So I can actually put $1,200 toward debt this month instead of $50. Score!”

So let’s talk about your checking account. My LMM co-host Andrew wrote a post defining his basic investing blueprint, and in it he stated that you should have 250% of what you spend each month on “stuff” in your checking account as breathing room.

Personally, I agree with this sentiment, though I modify it a bit. I want to have 250-300% of what I need after “fixed” expenses are accounted for – things like rent, bills, etc. I can come up with a hard number for fixed expenses, and I can automate them all – so I want my checking account to be filled after that number is taken into consideration.

You can go either way based on what you’re comfortable with – if you’re rolling with at least 2.5x your “number” that you got in the last step, you won’t be completely boned if something happens. That’s what you want to avoid. Being completely boned sucks, and is almost always a one-way ticket to massive credit card debt, crippling stress, or family members begrudgingly loaning you money.

One last thing here that you may be wondering:

“Don’t I need a savings account?”

The answer is… maybe. Here’s the thing: There isn’t much of a difference in the interest you earn on a savings account vs. a checking account. Based on inflation and what you can earn through investments, the interest from savings and checking accounts both might as well be zilch.

So, essentially, all a savings account does is complicate your finances. Andrew, my co-host, doesn’t think you need one.

However, having a savings account doesn’t hurt you (unless you have a shitty bank that charges you to keep it open – in which case you should leave that bank), so do what works for you. Since you’re probably a student, you might actually have a very good reason for keeping a savings account – it can act as a clear holding area for funds dedicated to guaranteed semester-ly expenses like textbooks and fees.

As for your emergency fund, this should be a reserve of cash that’s only for emergencies (buying the latest video game or deciding you want to go to Cabo are not emergencies). Now, nobody agrees on how these things should be set up, so I’ll just stick my own neck out and say try to have an extra $500-$1000 on hand. As a student who probably doesn’t have a family, you’re unlikely to have a huge emergency, so there’s no need to postpone paying off debt to build a huge fund.

I actually keep my “emergency fund” in my investment account. So, in terms of the pipeline, the top part of the fountain is the same as the bottom part. The crucial difference, though, is that I started paying off my debt after I’d hit that comfortable emergency fund level.

Now, some people might say it’s risky to keep my emergency fund in an investment. I’d agree – if I was investing in individual stocks. However, I’m a passive investor, and all my money is in mutual funds that are highly unlikely to drain overnight. There’s a bit of risk, but probability says I’ll be fine – and I have my checking account filled just in case.

Automate Most of the Process

With the pipeline model now firmly planted in your prefrontal cortex, you’re no longer unsure of what to do when you get paid each month. There’s now a clear picture of how that money should flow and where it should be allocated first.

Now, let’s take it a bit further. Let’s build a system that takes care of as much financial heavy lifting each month as it can, so we’re free to focus our attention on the things that matter – like Smash Bros.

The way I’ve done this is by setting up automatic payments on almost all of my monthly fixed expenses. I’ve got auto-pay enabled for:

- Rent

- Electric and gas

- Internet

- Cell phone

- All subscriptions – hosting, Spotify, etc

In addition to my fixed expenses, I also automate my investments. Each month, I’ve been auto-investing $500 into my Vanguard mutual fund. Just this morning, based on my goals, expenses, and current income, I actually increased that auto-investment to $1000/month – and it’ll need to increase further if I’m going to stick with my goal!

When I can, I route the expense transactions through my credit card so I can rack up cash bonuses. Ooh, that reminds me – I wanted to do an aside about credit cards.

Credit Cards

Credit cards, my friend, are powerful tools. A credit card is like a katana lent to you by your badass samurai grandpa. (What, you don’t have a badass samurai grandpa?)

Use it sparingly, only cut a few watermelons in mid-air, and clean it well on a regular basis, and that katana will stay in great shape. Ojiisan (Japanse for Grandpa) will be pleased.

Go around cutting too many watermelons and neglect to clean the blade, though, and you’re in trouble. Ojiisan will have his sword cleaned, even if it takes you five years of polishing.

The credit card companies, though, are evil Ojiisan because they actually want you to be in debt. That’s how they make money – through the exorbitant interest fees they charge. So they create all sorts of perks – like cash back rewards – to entice you to spend more on the card.

So, to not get into this too much, here are my hard and fast rules for using a credit card:

- Never use more than 20% of your credit limit in a month.

- Always pay the full balance on time, every month. Those people who tell you to carry a balance to build your credit score are wrong. I have NEVER carried one and my score is great.

To those, I’ll add an idea for you. It’s not something I do, but if you want to build credit while keeping your spending in check, it’s an option:

- Set some of your fixed expenses to be auto-paid on the card

- Set up auto-pay on the card itself from your bank account

- Lock the card in a drawer.

Think of your credit card as a different way to pay from your checking. It’s not a line of credit, it’s just a different way to pay – one that’s a bit more complicated but that can have some benefits.

The last thing I’ll mention here is that I don’t auto-pay my credit card. Since I use it for day-to-day expenses, I always want to make sure I’m aware of what my balance is and when it gets paid. To that end, I have a recurring monthly task in Todoist to go in and pay my card, and I also have a weekly habit in Habitica to check up on my entire financial picture in Mint.

For a full explanation of how credit cards work, check out this guide.

Save for Non-Regular Expenses

As I mentioned before, one thing you have to deal with in college is semester expenses. These expenses don’t happen every month, but they can be substantial, so you need to plan for them.

Each semester, you’ll probably need to buy/pay for:

- Textbooks

- Fees

- Tuition

- Dorm fees, unless you’re in an apartment

- Supplies

It’s essential to plan for these expenses ahead of time. How are they going to be paid?

You might have student loans coming in each semester to pay for this stuff (though if you do, make sure you understand the true cost of them). You may have scholarships and grants. Maybe Mom and Dad are still paying for it all.

Whatever your funding source is, make sure you know what it is and know whether or not it’ll cover these non-regular expenses. If it won’t, you’ll need to modify your money pipeline a bit with a saving goal to deal with them.

Oh, and if you end up with extra money from scholarship, grants, or loans, it should go into the pipeline as well. If it gets past the Emergency Fund, and it’s subsidized (meaning you don’t need to pay interest on it until after graduation), I’d probably put it in a savings account unless you’re close to graduation and know you won’t need it for a future semester’s expenses. In that case, you can start paying off debt or maybe even invest it.

Get Your Spending Habits in Check

Alright, this is the point in the process where most people start getting stressed with their budgets. Once your fixed expenses are taken care of and your saving quotas have been met, what’s leftover is yours to spend… but remember, you’re aiming to have 2.5-3x of your “number” in your checking account at all times.

People get stressed here because their spending habits don’t match up with their goals. So they sit down at the end of the month, pout about how much they spent on Starbucks lattes and restaurants, and declare – ONCE AND FOR ALL! – that they’ll cut down their spending from here on forward.

Then they’re right back at Starbucks the next morning because,

“I’m really in a rush today – I’ll start making my coffee at home tomorrow, I swear.”

Now, here’s the thing – I’m not against buying Starbucks lattes. I buy coffee at my local coffee shop 2-3 times a week. If there’s something you like, and you can afford it after all your important financial goals are taken care of, then let yourself buy it! We’re not on this earth to drive numbers in a bank account as high as they can possibly go – money is a tool you should use to build a happy life. So drink your $3 coffee if it makes you happy and if doing so is still below your means.

What I’m getting at here is that habits are powerful. Sitting down and creating a strict budget is not likely to change them. Rather, you need to start building changes into your daily routines and attacking the habits at their roots.

One very easy way to do this is to pay for everything in cash. Using a credit card makes it difficult for you to appreciate how much money you’re actually spending; when you use cash, you see the individual dollars leave your wallet. You can actually see how much is left when you peer into the billfold or your purse.

If you want to go further than that, start writing down every purchase you make. You can carry around a small notebook for this (that’s what Martin does), or you can use an app like Spending Tracker for your smartphone.

This manual tracking has been well-documented as a successful habit changer in weight loss, and I’ve heard from many people who say it works for spending as well.

The idea is to make tracking the expense an integral part of the routine portion of your spending habit. When you experience the trigger – the urge to buy something, the process should go like this:

- Decide whether the purchase is a good decision

- Buy the thing

- Record the transaction

- Get the reward

Without recording the transaction, it’s easy to fail to realize the cost of getting that reward – and so the spending habit continues unchanged.

You can also get into habit tracking. One idea would be to use a tool like Habitica to track your progress in recording your transactions. Or you could set a daily spend cap and use it to punish yourself if you surpass it. Build a reward for saving money and you’ll do it more.

Looking for even more ways to save money? Here are 25 things you can do.

Plan and Research to Cut Expenses

In addition to modifying your spending habits, you should also seek out ways you can lower non-regular expenses.

In college, there are a ton of ways to do this. I’ll just list a few:

- Find the cheapest textbooks – at the very least, use a comparison tool like StudentRate to find the best prices

- Utilize student organizations to do fun things at a subsidized cost

- See if you could reasonably graduate early

- Take some inspiration from my friend Aaron’s DIY home office

Yay, frugality! Oh, I should mention that StudentRate is also a good place to look for deals on other items besides textbooks, so check it when you’re looking to buy new stuff. You might find a discount. There are probably other student discounts floating around your campus as well, so keep an eye out!

If you want to get even further on the frugality train, my podcast interview with Kristin Wong of Brokepedia is a good place to start. Also, you may enjoy this (huge) post:

39 Ways You Can Cut the Cost of College

Don't let college become a giant money-sucking space robot. Save money with these strategies.

Wrapping Up

So, with that, you should have a good idea of how to start “budgeting” as a student. Now, there are a lot of other topics related to this one, and you might have some leftover questions. I’ve already written a lot here, so a lot of these related things don’t fall within the scope of this article – but I’m going to answer some of them rapid-fire style anyway.

- How should I pay off my debt? – Use the Stack Method: Pay your minimums and direct extra funds to the loan with the highest interest rate first. Use a tool like Mint to track your progress and stay motivated.

- Where should I invest my money? – Now that’s a can of worms. I’m a fan of passive investing, so to keep it simple I’d say Betterment or Vanguard. Betterment is probably the absolute simplest, though it’s got a slightly higher expense ratio. I’ll write more about this sometime soon.

- I still think I should make a budget. What should I do? – Well, if all this still isn’t enough for you, I’ve heard good things about You Need a Budget. Or, check out our full list of the best budgeting apps.

- What tool do you use to keep on top of your finances? – I use Mint to make sure everything’s looking good, and I check it once a week.

- How can I make more money? – Check out 25 ways to make an extra $1,000 per month (great if you’re in a hurry) and our guide to 100+ ways to make money in college (if you want to read a huge, in-depth list).

Want to learn more? Do these two things.

Firstly, I’ll be writing more about managing your money in the future. To get notified when I do, sign up for the College Info Geek newsletter. When you do, you’ll also get a free copy of my 100+ page book 10 Steps to Earning Awesome Grades (While Studying Less).

Secondly, I co-host a podcast entirely about money called Listen Money Matters. New episodes come out three times a week, so if you’re looking to learn more about your finances, start listening!